Exploring the Past — The Woman’s Building

Spending the summer of 2012 in Santa Fe, where I had lived from 1980 to 1993, brought back memories. In that dry, arid climate I was flooded with memories of my years in New Mexico. It was a period of reflection and contemplation.

One day in July I walked into a Santa Fe art gallery where Judy Chicago’s Power Play, a body of paintings from the 1980s, was on exhibit and I was transported to my years in California immediately preceding the move to New Mexico. As a student at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, I had been one of the many volunteers who worked on Chicago’s The Dinner Party, the opening of which I attended at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. My recollection was made more vivid by an interview I read in the June/July 2012 issue of Art in America, about artists and activism. The interviewee was Suzanne Lacy whom Chicago mentored in California in the early 1970s. Also, I happened to bring to New Mexico a copy of But is it Art? The Spirit of Art as Activism edited by Nina Felshin that included a chapter on Lacy.

I first met Suzanne in the mid 1970s in San Francisco. I had recently graduated with a BFA in Painting from the San Francisco Art Institute and was working on Teaching Credentials, K through 12, at San Francisco State University. I was also the mother of a toddler. I had taken a workshop at the Art Institute with members of the Feminist Art Workers who, together with Suzanne Lacy, had been students at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles soon after it was founded by Judy Chicago, Sheila de Bretteville and Arlene Raven in 1973. (For more on the groundbreaking work done at the Woman’s Building and an exhibition, “Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building,” see: this LA Times article.

In 1977 shortly after the workshop at the Art Institute, Suzanne contacted me. She was seeking assistance for a performance about Picture Brides, as well as the Asian women who were smuggled into the country to becomes prostitutes and slaves, entitled “The Life and Times of Donaldina Cameron.” Picture Brides were the Chinese women whose photographs were sent to Chinese men in the United States. The men would make their selection from the photographs and the women were then shipped off to the States arriving at Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, the point of entry for Asians coming to America. Suzanne’s performance required a boat to sail from San Francisco to Angel Island and back. I was given the task of finding the boat which, along with a boat man, was eventually found and the performance took place as scheduled. Suzanne, dressed in a severe black gown and bonnet, played the role of Donaldina Cameron, a nineteenth century missionary who worked among the Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. Kathleen Chang, a young Chinese woman, played the role of a picture bride. The performance took place on a ferry to Angel Island, a boat sailing alongside it and on a hilltop on Angel Island. As the audience boarded the ferry I distributed a broadsheet with turn-of-the-century photographs and stories about Asian women who were smuggled into the country or who came as Japanese war brides. Looking back on the events of that day, it is ironic that the boat owner took a fancy to me and insisted on holding my hand throughout the boat ride. It was ironic because, besides being married at the time, I was an ardent feminist and yet I felt compelled not to alienate him at any cost. Without him the performance could not take place.

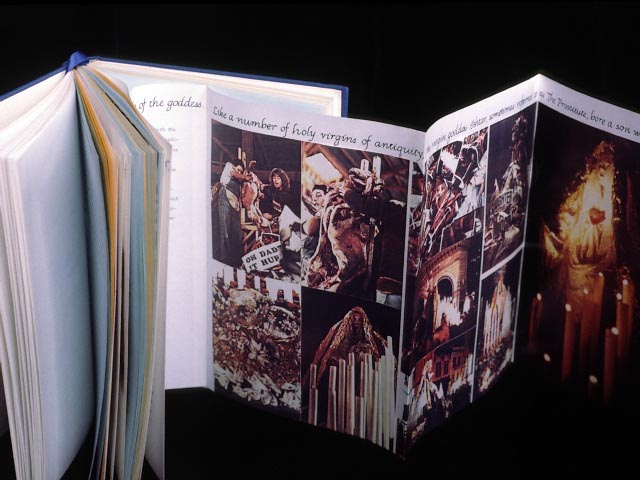

Suzanne stayed at our little Victorian house on Potrero Hill the evening before the performance of “The Life and Times of Donaldina Cameron.” During our work together on a subsequent project, “The Virgin and the Whore,” Suzanne and I made the long trip between Los Angeles and San Francisco in her truck sporting a bumper sticker, “Support the right to arm bears.” We talked about many things. Suzanne compared her commitment to women’s issues with a missionary’s zeal. It was then that she advised me to move to Los Angeles and become a student in the Feminist Studio Workshop at the Woman’s Building and work on an MA through Goddard College while completing my Teaching Credentials. Not long after our discussion I made the move to Los Angeles, leaving my young son in San Francisco in the care of his father, returning whenever I could to visit him and bringing him to L.A. to stay with me as often as I could. Of course I missed him terribly but I threw myself into my work on my master’s thesis, The Story of M, which explored motherhood from a variety of perspectives including mythical, historical, sociological and psychological, all from a feminist’s point-of-view. I contrasted my Story of M, with its focus on strong, autonomous women with Pauline Reage’s The Story of O, about a female masochist, published a few years earlier and causing a disgruntled reaction in the burgeoning women’s movement.

In 1978, while I was a student at the Woman’s Building, I – together with other Feminist Studio Workshop students including Ann Klix, Betsy Irons and Monica Mayer – worked with Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz on the Virgin and the Whore float and performance.

The following is a description from Suzanne Lacy’s website:

“’Take Back the Night’ revealed the Madonna/whore dichotomy that inspires pornography. The first national “Perspectives in Pornography” conference was an important opportunity to include women visual artists in political organizing. Ariadne: A Social Art Network [a group of artists formed by Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz] invited artists from around the state to offer events, performances, and exhibitions for the conference planned by Women Against Violence and Pornography in the Media. Motion, a San Francisco performance collective [a group to which I had belonged when I lived there], organized a panel on female eroticism and art and created rituals to open and close the conference… On Saturday evening Lacy and Labowitz along with Monica Mayer, Rose Marie Prins, Betsy Irons and Ann Klix created a mass public performance for 3000 women marchers who left the conference and marched on the Broadway strip, San Francisco’s porn district. There they greeted a brightly lighted float with chants and ululations. Holly Near sang “Fight Back” as a two-sided float moved slowly through the crowds–its front a Madonna bedecked with flowers and electric candles after the Santa Semana celebrations in Latin America and its back a three-headed lamb carcass, like the goddess Hecate, whose open gut cavity leaked layers of black and white pornography. Marchers ripped the pornography from the back of the float as it went by.”

Also in 1978, I attended a series of performances and a conference in Las Vegas with several other students from the Woman’s Building. The following is an excerpt from Lacy’s website:

“With its high incidence of violent rape and its global image as the epitome of feminine objectification, Las Vegas was the perfect setting for a performance demonstrating the continuum between objectification of women and violence. Two billboards, a media campaign in the local press, and a half-hour PBS documentary created a broad community exposure to the issues of the performance. Events were created to appeal to special audiences including show girls. Leslie Labowitz designed a media event in front of a billboard by Las Vegas artist Deborah Feldman. The Feminist Art Workers created “Traffic in Women,” a bus tour/performance that brought fifty Los Angeles women to one of the weekend events. The Los Angeles City Council passed a notice of commendation delivered to the Las Vegas City Council. The event, sponsored by the Nevada Committee for Humanities, included a daylong conference that included Margo St. James, founder of COYOTE prostitutes’ union. An art exhibition in the University gallery on the theme of violence included … Suzanne Lacy’s ‘There are Voices in the Desert.’”

These experiences, and the (then) fledgling women’s movement’s ethos that prioritized content over form in art, were among the many during that period that had a profound influence on me. In the years since I have facilitated numerous projects, both independently and as an Artist-in-Residence in New Mexico, Virginia, California and Florida, that were inspired by the women I met through the Woman’s Building and the work we did there.

“Sacrifice of the Son,” performance at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1978, inspired by my learning experiences at the Woman’s Building