Collaboration: The Whole is Always Greater Than the Sum of its Parts

This article, a combination of a few of my blog posts relating to collaboration, will appear in an upcoming edition of Arts Coast Magazine, Creative Pinellas’ on-line magazine:

For well over two decades both making art, mostly mixed media paintings and sculpture, and teaching art, have been my focus. While I have done hundreds of residencies as an Artist-in-Residence with the New Mexico Arts Commission; VSA New Mexico and Florida (now Arts4All); the Virginia Commission for the Arts and Youth Arts Corps in Pinellas County, Florida, as well as independently, working with people of all ages and abilities, in institutions ranging from elementary schools to colleges to a Navajo reservation, and prisons, some of my most memorable residencies are of collaborations.

Linda Piper and I were Artists-in-Residence in New Mexico in the 1980s and early 1990s. She, at that time, was a theater director and story teller. We collaborated on four projects during our years as Artists-in-Residence. The first, an interdisciplinary event at New Mexico Arts Commission’s annual conference, cemented a friendship that continues to this day.

After that we worked on a play, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, with students in an elementary school who adapted the classic children’s book. Since it was a short residency we decided to go with a familiar story rather than work with the students to write their own play, as we did during longer residencies.

Reminiscing about our experience more recently, Linda commented on how, in collaboration, the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts. She commented on how involved the students were in the process, contributing ideas that added to the success of the project. The one element that still stands out for both of us was a huge three-dimensional head that the students and I worked on together. It had a mass of hair, a large red mouth and an outstretched hand with a wagging forefinger. This represented Max’s mother. It was a hit with the actors and audience alike.

During a much longer residency at an elementary school in Farmington, New Mexico, Linda and the students wrote a play titled Masks. It evolved out of a discussion Linda had with the students about tension in the community between the three primary ethnic groups: the Anglos; the Hispanics and the Native Americans. From there the discussion broadened to encompass issues of not only racial stereotyping, but stereotyping in general.

Meanwhile, I worked with another group of students on sets and huge sculpted heads that represented various stereotypes.

The action took place on a school playground during recess and, as the various stereotypical characters appeared on stage, so the corresponding giant head would be raised by a student standing at the foot of the stage. The play enabled the students to explore their prejudices and come to an awareness of the unique individuals behind the stereotypical roles that breed separation and difference rather than unity and accord.

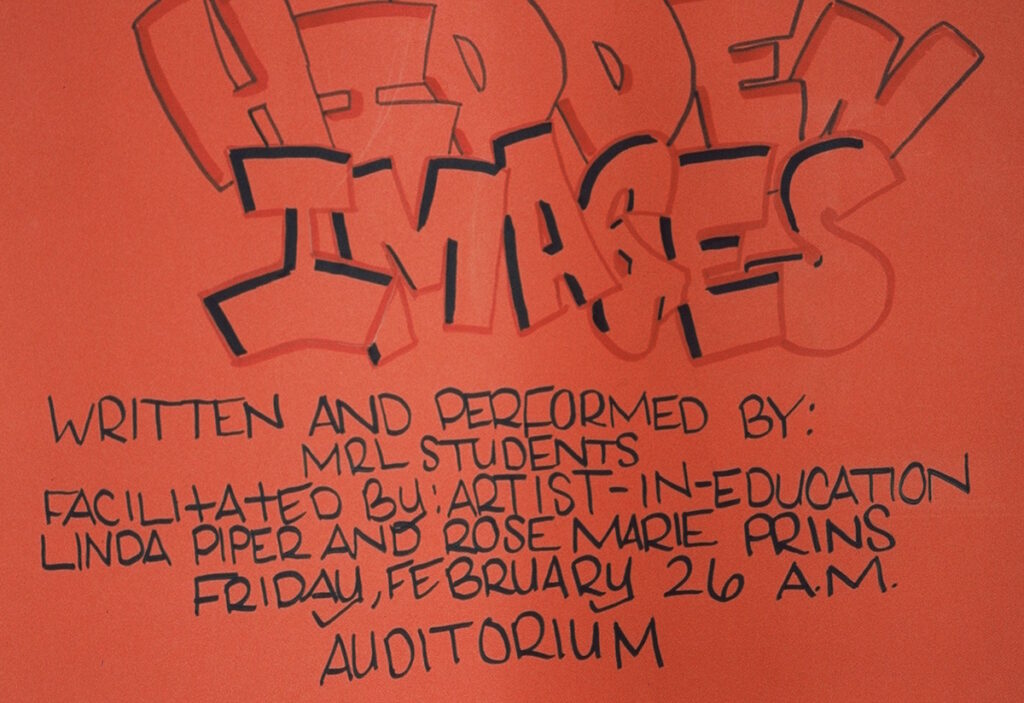

Our most challenging but also the most rewarding residency was at the New Mexico Youth Diagnostic and Development Center in Albuquerque where we worked with teen offenders. Once again Linda worked with the young actors to write a play. They titled it Hidden Images. I worked with a different group to create a backdrop, publicity materials and masks. The masks represented the façades youngsters adopt to help them cope with peer pressure, low self esteem and the related behavioral problems, such as bullying, that so often spiral out of control.

We’ve all heard the expression, “the show must go on,” well, our show almost did not go on! Shortly before the scheduled date of the performance the sheriff arrived to release the star of our play. The youngster begged to remain incarcerated until after the performance! He prevailed, and the play was performed as scheduled to an enthusiastic audience. I often wonder what happened to that young man, and to the many other young people I’ve worked with as an artist and as an artist-in-residence over the years. Now, thanks in large part to social media, I don’t have to wonder about all of them—I’m still in touch with several of the students I’ve worked with over the years, some of whom I still mentor.

Some time after arriving in Florida, I became an artist with Creative Care’s Arts in Healthcare program. A small group of visual artists, dancers, musicians and a choreographer, made art with patients at Ronald McDonald House, Benedict Haven, All Children’s Hospital, and St Anthony’s Hospital.

A memorable project I did as a Creative Care visual artist was at All Childrens’ Hospital in St Petersburg in collaboration with Creative Care dancer/choreographer Paula Kramer. The project was entitled The Magic Tree. Participants, who were parents and siblings of young patients, were led by Paula in dance moves to establish the theme. Through movement Paula evoked the sun, the rain, a rainbow, gentle breezes, birds, bees and butterflies; also the growth of a tree from tiny seed to a full grown fruit tree with branches and leaves supporting a variety of animals and insects.

Then the participants, ranging in age from one year to seventy-something, joined me to finger-paint a large painting with all the elements they had just danced into being. The Magic Tree painting was displayed in the spring in a central location at the hospital. Passers-by could, for a moment, forget the stress of their jobs as healthcare workers or, if they were relatives of patients, the anxiety of having someone they loved hospitalized, and enjoy our magical spring scene.

The following is an excerpt from an email I recently received from the Vice President of Mission of one of the hospitals Creative Care Arts in Healthcare worked in: “I can’t thank you enough for sharing your expertise, experience and compassion with us and our patients. You certainly played an important part in the healing for the whole person… Thank you for being such a blessing… You have displayed for us the important value of Art in the Healing Process.

With much gratitude,…”

Several years ago I worked, with the assistance of a local artist Michelle Stone, on a project for the Greater Palm River Community Development Corporation whose mission is to build a better community by investing in children and families. Together with several adults and teens Michelle and I attended a performance of South African playwright Athol Fugard’s ”My Children! My Africa!” at a Tampa theater. For many, this was the first professional theatrical production that they had attended.

My Children! My Africa! was written in 1989, shortly before apartheid ended. The play is a “blow to the gut” of black and white audiences alike. It is both a cry for tolerance and a bitter acceptance of the violence that flared to destroy an uneasy peace in South Africa. It’s impossible to ignore the parallel between the Mr. M in the play, and his search for change through peaceful and intelligent intervention, and the Mr. M who became President Nelson Mandela.

In a small town in the Karoo area of the Eastern Cape Province, in a classroom of the black Zolile High School, Mr. M referees a student debate contesting that women should not receive the same education as men. In favor is Thami, one of Mr. M’s favorite and most promising students.

In opposition is Isabel, a white student visiting from an all-girls’ school. Mr. M sees potential in the intellectual pairing of Isabel and Thami, and brings them together as a team for the statewide English literature competition.

As they prepare under Mr. M’s tutelage, Isabel gains immense respect and admiration for Mr. M and forms a friendship with Thami. Outside the classroom Mr. M’s hopes for Thami are challenged by their generational divide and increasing political unrest under the South African government’s policy of apartheid. Thami quits the competition when he joins a student movement to boycott the school until blacks are given an education equivalent to that of whites. The tradition-bound Mr. M regards Thami’s actions as destructive and cooperates with the white police by informing against the boycotting students. Thami’s comrades retaliate; a mob approaches Zolile High School, intending to kill Mr. M for his betrayal. Thami tries to help Mr. M escape by offering to vouch for Mr. M’s innocence, but Mr. M refuses the protection of a lie and stands his ground. The mob kills him.

Isabel struggles to comprehend why it seems the black community is tearing itself apart. She sees Thami one last time after Mr. M’s murder and learns that Thami plans to flee the country to avoid arrest so that he can continue fighting against apartheid. Isabel is left alone to pay her respects to the memory of Mr. M.

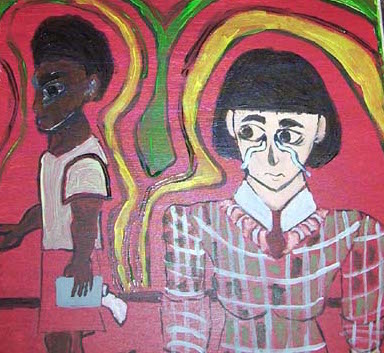

After discussing the play, participants spent a Saturday afternoon creating acrylic paintings. These were displayed in the theater lobby for the run of the play. Later, the paintings were displayed on the walls of the Children’s Board of Hillsborough County offices in Ybor City.

One of the most touching scenes Michelle and I witnessed that Saturday afternoon was the youngest participant, a girl, laboring with such concentration on her image depicting unity between two individuals of different races. Her mother’s painting, a silhouette of the continent of Africa with diagrammatic faces of people of all races and the slogan, “Raise Your Voices, Lower Your Weapons,” was the perfect complement to her daughter’s image: the mother’s painting portrayed the universal aspect of the theme, the daughter’s the personal.

My hope is that this project, and the dozens of others I’ve worked on, both individually and in collaboration, be they about ending racism, bullying, or about caring for our planet, made a lasting impression on the participants and viewers.

Tags:Blog post relating to collaboration appearing in Arts Coast Magazine. Linda Piper, Creative Care, My Chilidren! My Africa!, New Mexico Youth